FEDERICO FELLINI from drawing to directing

Federico Fellini on set

On the 130th anniversary of the birth of cinema, an exhibition showcasing the graphic work of the iconic Italian director.

In the 1940s, he supported himself by drawing caricatures, capturing scenes from everyday life on paper that he would later film on set, and he did not stop even when a stroke at the age of 73 forced him into hospital. This is a previously unseen side of Federico Fellini, as revealed by the exhibition FEDERICO FELLINI. From drawing to directing, which, at the MuSa Museum in Salò, brings together about 50 drawings, cartoons, and caricatures penned on paper by the great director—many of which are being exhibited for the first time in Italy—together with a photographic corpus, also almost unpublished, of shots portraying him on the sets of his films.

Curated by Elena Ledda and Federico Grandesso, and thanks to a range of prestigious collaborations (Fondation Fellini pour le Cinéma – Sion, Switzerland, Fellini Museum Archive in Rimini, Media Museum in Pescara, Francesca Fabbri Fellini, director and granddaughter of the great Federico, and Anna Cantagallo, who cared for the Maestro in the summer of 1993), the exhibition documents the very close link between the designs and the masterpieces on film that consecrated the author in the Olympus of world cinema. The narrative also includes the genesis of collaborations and friendships that blossomed on set, with artists of the caliber of Nino Rota, Nino Za, and Ennio Flaiano, who helped define the textual, musical, and scenographic forms of his film production.

FELLINI AND CARICATURE

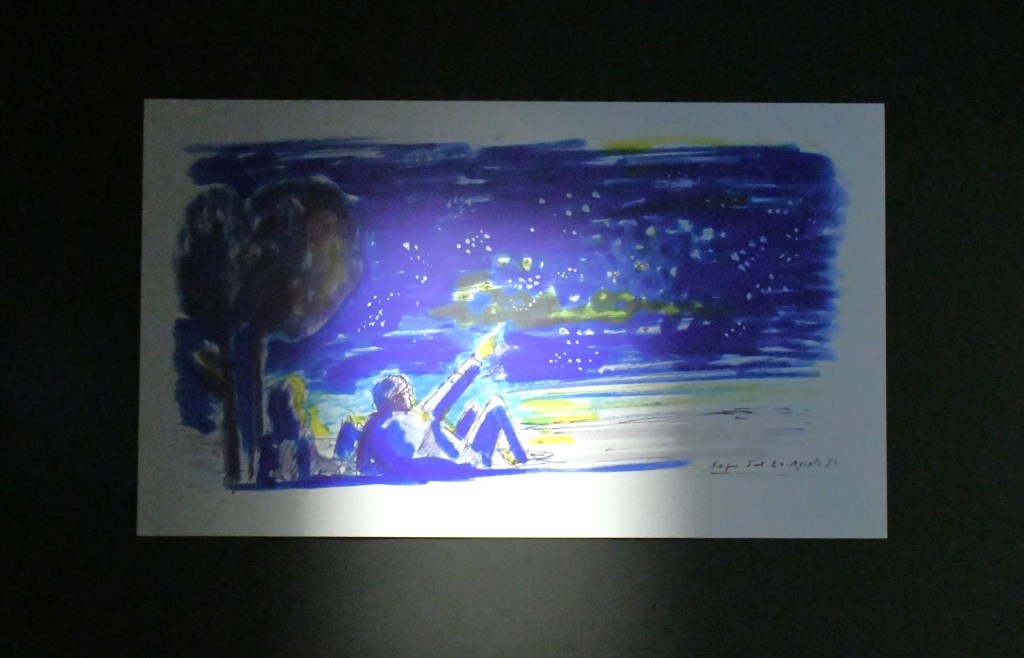

From adolescence to maturity, caricature accompanied every stage of the director’s personal and professional journey. Federico Fellini was only 16 years old and attending high school when the manager of the Fulgor, the cinema in the city of Rimini, commissioned him to draw portraits of actors and famous people. This phase of his career is documented by three This phase of his career is documented by three examples of Caricature for Cinema Fulgor, dated 1937, Caricature of Italo Roberti (1938), and Caricature of George Murphy (1937/1938). Even after achieving international success, drawing was always his initial approach to sketching the characters and personalities of his films. Examples of this include Disegno di scena, Il passaggio delle Mille Miglia nel borgo (for Amarcord), numerous self-portraits, and the unpublished drawings Casanova and Pinocchio, from 1982. Among the most iconic is Sogno, 20 agosto 1984 (Dream, August 20, 1984), taken from the Libro dei sogni (Book of Dreams): a diary in which the great director gave graphic form to his dreams and nightmares from the late 1960s until August 1990.

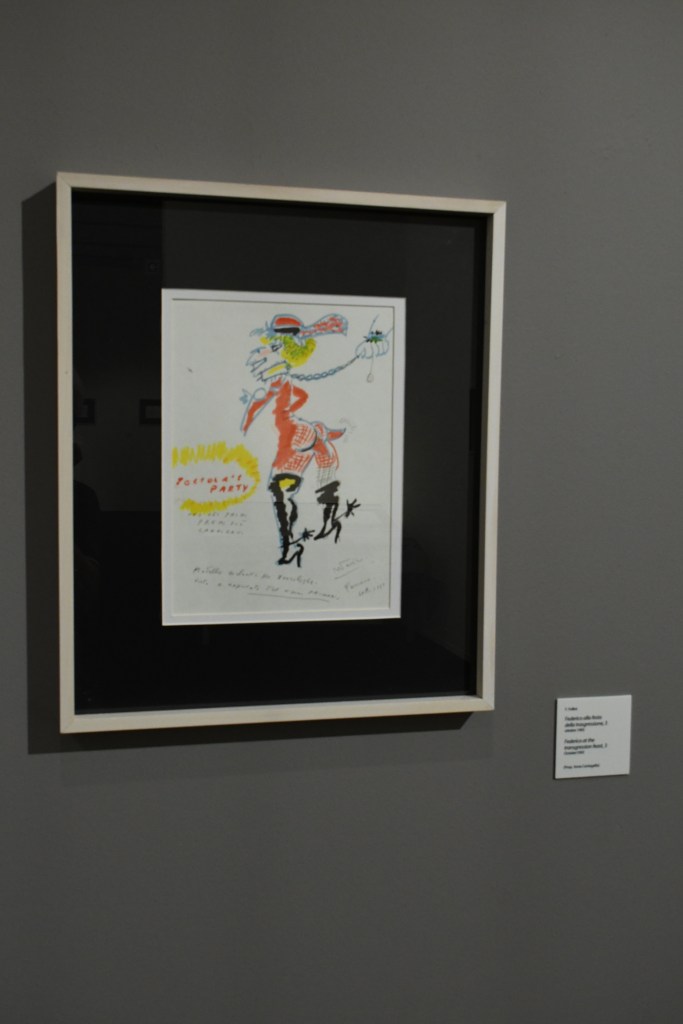

The dream theme is also present in Sogno. Il viaggio di Mastorna (Dream. The Journey of Mastorna) and Sogno. La morte del clown (Dream. The Death of the Clown). The section also includes the drawing Testimonianza (1992) in which Nino Za – a well-known illustrator, caricaturist, and mentor to Fellini – depicts the director of La Dolce Vita advancing towards an interior populated by characters. In addition to the posters and billboards of Fellini’s films, the section is preceded and completed by the screening of Fellinette (2020, Animation 12 min): a short film by Francesca Fabbri Fellini in which a little girl drawn in 1971 by her uncle is the protagonist of a fairy tale set on the beach in Rimini on January 20, 2020 (the centenary of the birth of the great Maestro).

CASANOVA AND AMARCORD: “CULT” FROM PAPER TO FILM

Ad Amarcord (1974) sono riconducibili diverse opere in mostra, tra le quali Durante Amarcord e i tre studi per il personaggio della Volpina, interpretato da Josiane Tanzilli, oltre a uno dei molti scatti di Pierluigi Pratulon (1924-1999) – fotografo ufficiale dei set felliniani – che ritrae il regista col collega Andrei Tarkowski durante le riprese. Al celeberrimo Casanova, nell’anno in cui ricorrono i 300 dalla nascita del seduttore veneziano, sono dedicati i disegni preparatori per l’omonima pellicola diretta dal regista nel 1976. Accanto ai tre disegni di Casanova vecchio e allo schizzo per la Scena della “merlettiera” si trovano le fotografie che immortalano Fellini sul set del film accanto a Gérald Morin, suo assistente e segretario privato di lunga data, Alberto Moravia, Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica e agli attori Cicely

Browne, che nel film interpreta la marchesa Durfé e Donald Sutherland nei panni del protagonista. La sezione include inoltre l’emblematico disegno Prova di personaggio principale per Gian Maria che testimonia come, prima di affidare il ruolo a Sutherland, Fellini avesse considerato Gian Maria Volonté per il ruolo di Giacomo Casanova. Disegni e fotografie provengono dalla Fondation Fellini pour le Cinéma, istituzione culturale con sede nel Cantone Vallese, sorta in seno alla collezione privata di Gérald Morin che raccolse materiali sul regista italiano a partire dal 1963.

THE LATEST DESIGNS

Two rooms are dedicated to the drawings made during the last period of Fellini’s life, particularly during his stay at the clinic in Ferrara, where he was admitted following a stroke in 1993. On display is a selection of 29 sketches, drafts, and scene ideas on A4 printer paper, exhibited for the first time in Italy thanks to Dr. Anna Cantagallo, a physiatrist and neurologist who treated the Maestro in the summer of 1993. The works—including Anna, the “angel” woman and Federico, Anna with the whip and Federico, Anna “the blonde” and Federico, Federico walks alone, Line of the path, Federico on the cableway, Federico and the triangles – show a double register. On the one hand, the tests and exercises of Fellini the patient, who shows difficulty in following the rules and plays with lines and colors; on the other, the free drawings, where lines, colors, and writing give shape to fairy-tale illustrations, grotesque, self-portraits and stories born in the wake of the doctor-patient relationship, so much so that “Doctor Anna” becomes an integral part of his repertoire of illustrated characters. A journey lasting several months which, beyond its underlying therapeutic value, highlights the great director’s desire to continue to express himself and tell stories through his inexhaustible artistic vein.

You must be logged in to post a comment.